Heather Cox Richardson’s “Letters from an American” on March 17, 2025, documented the current US administration’s removal of content related to people of colour, women, and anyone else considered “DEI” from government websites, including figures buried in Arlington Cemetery and the Navajo code talkers. This is a real and present instance of the historical erasure my research seeks to counter. My edition of The Need for Heroes: Black Intellectuals Dig Up Their Past was published in 2024 precisely to amplify Black scholars’ voices and ensure the preservation of historical narratives about soldiers and maroons of African descent, narratives that must be repeatedly shared and republished to prevent their being forgotten. That same year, I also published Heroes Sung and Unsung: Black Artists in World History. The title speaks for itself.

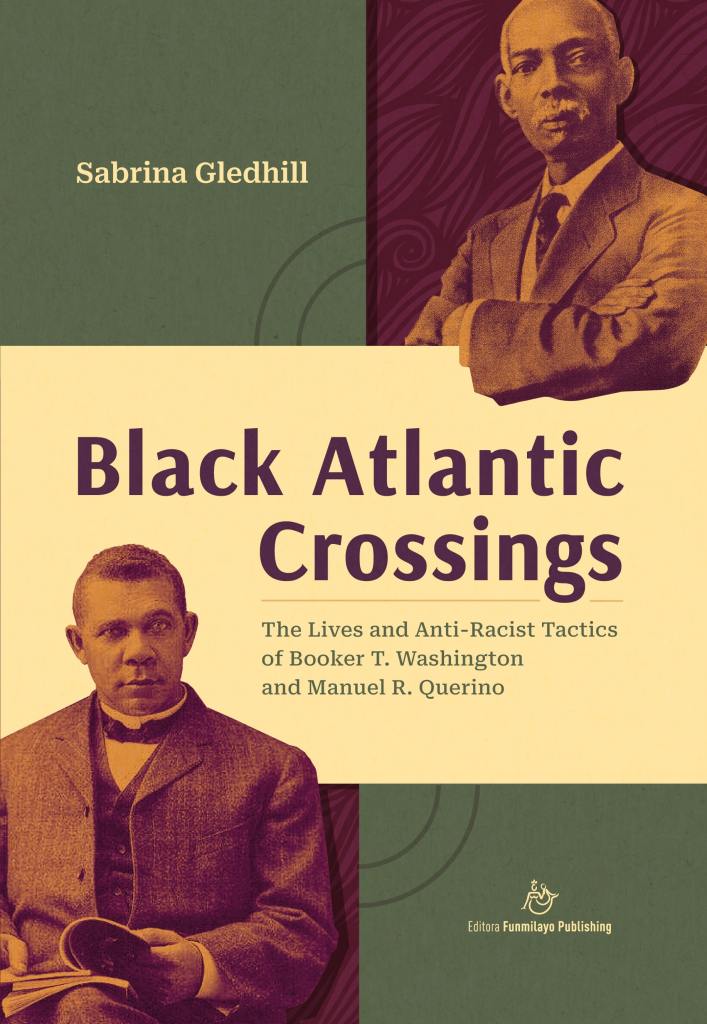

Carrying on this work, my forthcoming publication, Black Atlantic Crossings: The Lives and Anti-Racist Tactics of Booker T. Washington and Manuel R. Querino, expands on these themes. Here is the genesis of this book:

In the mid-1980s, I stumbled upon a figure who was largely unknown outside Brazil. Manuel Querino, an Afro-Brazilian polymath, was quoted in the epigraph to Jorge Amado’s Tent of Miracles. As I was then pursuing an MA in Latin American Studies at UCLA, I mentioned Querino to my supervisor, the esteemed E. Bradford Burns. It turned out that he had not only published an article about Querino and translated the introduction to one of his works but he had also featured Querino prominently in his History of Brazil. Rather than a biography, Professor Burns encouraged me to delve into a comparative study, contrasting Querino’s perspectives on Africans and their descendants with those of other Brazilian intellectuals active before 1930—a pivotal year when the academic study of Africans and their descendants gained acceptance in Brazil. These intellectuals included Nina Rodrigues, whom I positioned at one extreme of the spectrum of “racial pessimism,” with Querino at the other. Nina not only believed in Black inferiority but also that mixed-race people were destined to die out due to their moral and physical frailties.

In late 1986, I went to Brazil for preliminary PhD research and ended up staying for twenty-eight years—but that’s another story . While I hadn’t planned to continue studying Querino, I was incensed by the distortions of his legacy. Worse than being erased, his reputation had been actively tarnished by overtly racist interpretations of his life and work. For example, it was wrongly assumed that he died a pauper and was insignificant because he was buried in a “poor people’s cemetery” (a claim proven inaccurate). Academics cast doubt on whether Querino was the inspiration for Pedro Archanjo, the protagonist of Amado’s Tent of Miracles. His scholarly output was also underestimated. Meanwhile, Nina Rodrigues was celebrated as the father of anthropology in Brazil. Fortunately, I was not the only one who was passionate about defending Querino’s memory and retelling his story—accurately, this time. Scholars like Jaime Nascimento and Maria das Graças de Andrade Leal were also writing and editing books about him. Nascimento organised seminars and lectures and graciously included me in the line-up of speakers.

By the time I finally went on for a PhD at the Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA) in 2010, Leal had published a biography of Querino focussing on his work as a politician and labour leader. My interest was still focussed on his defence of Africans and their descendants, but since my PhD thesis had to be “original”, I decided to compare and contrast Querino with Booker T. Washington, a Black educator the Afro-Brazilian scholar specifically admired. The result was a study that was published in Brazil in 2020 as Travessias no Atlântico Negro: reflexões sobre Booker T. Washington e Manuel R. Querino. An expanded, updated translation is now in press, entitled Black Atlantic Crossings: The Lives and Anti-Racist Tactics of Booker T. Washington and Manuel R. Querino.