More than 40 professionals, mostly Black journalists, worked for over two years and eight months to produce the Querino Project, a series of podcasts and text feature stories that offer an Afro-centric look at history to explain Brazil today. The eight episodes are on air and have already been downloaded 810,000 times as of Oct. 28, 2022. The podcast has reached first place in both Spotify and Apple’s daily rankings of the most listened-to podcasts in Brazil.

“Querino has no journalistic scoop. No information is being revealed for the first time. Researchers have been publishing for a long time, some more recently. The big impact is one of novelty [to a wider audience]. We are learning things. Things that I, Tiago, even working from this viewpoint since 2018, didn’t know,” journalist Tiago Rogero, the creator of the project, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

This is the third venture of Rogero, 34, into the world of non-fiction podcasts focusing on Afro-Brazilian culture and characters. In 2019 he produced Negra Voz, for O Globo newspaper, which won him the Vladimir Herzog Prize for Journalism and Human Rights in 2020. Then, he produced 30 episodes of Vidas Negras for Spotify.

One of the inspirations for Project Querino is the New York Times’ Project 1619, which similarly places the consequences of slavery in the United States at the center of the national narrative. Project 1619 refers to the year that the first slave ship landed in the United States bringing enslaved Africans. The event occurred one year before the celebrated arrival of the Mayflower ship with European settlers, which has a privileged place in American historiography.

“Every American child learns about the Mayflower, but virtually no American child learned about the White Lion [the ship that brought the first enslaved Africans to the country],” journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, editor in charge of Project 1619, told NPR. “Blacks are largely treated as an asterisk in American history.”

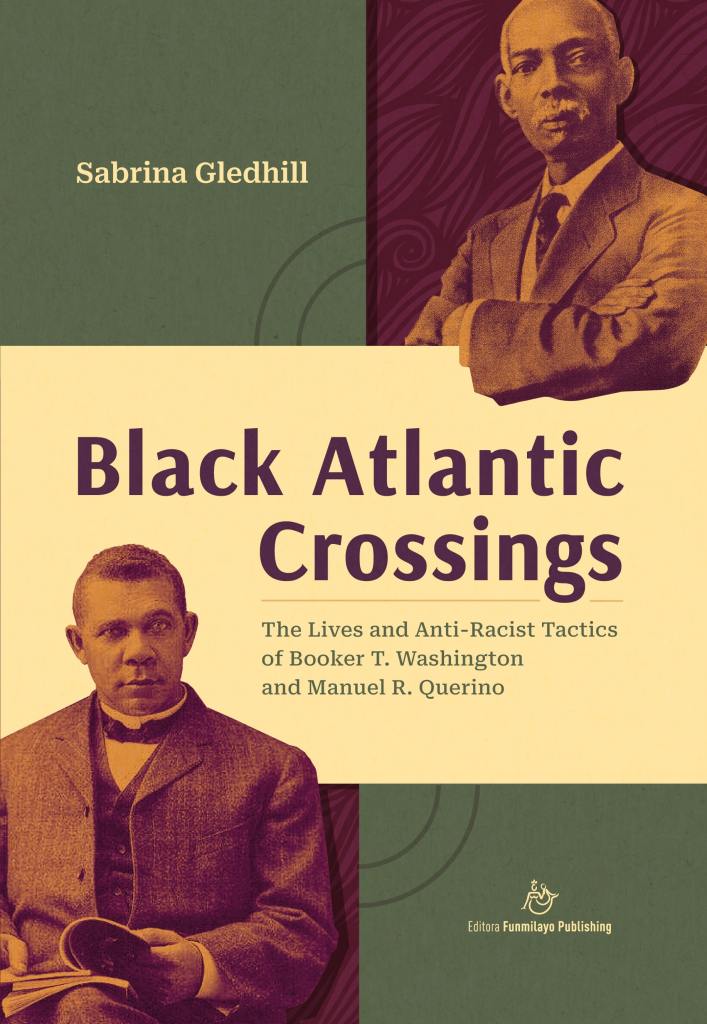

Similarly, the Querino Project presents Black historical characters who are little known in classrooms. The name Querino is a tribute to one of them, the intellectual Manuel Querino, a Black man born free in 1851 in Bahia, in a Brazil that was still a slave country. Brazil abolished slavery completely only in 1888, and was the last country in the Americas to do so.

Querino distinguished himself as a journalist, teacher, artist, and politician. He published in 1918 the book O colono preto como fator da civilização brasileira [The Black settler as a factor in Brazilian civilization], a social sciences’ pioneering text which placed Afro-Brazilians in a protagonist role in the building of the nation. Before starting the research for the Querino Project, Rogero himself did not know who the Brazilian intellectual Manuel Querino was.

“He is the exception of the exception of the exception because he was a Black child who had the chance to study. Because of this he became a geometric drawing teacher, an artist, researcher, journalist, union leader. He has an incredible intellectual production that positions Afro-Brazilians as protagonists in the process of nation building, and not just as a mere accessory, which is what the official version of history at that time already did,” Rogero said.

Manuel Querino is introduced to the audience only in episode four of the podcast, O Colono Preto [The Black settler], in which Rogero delves into the roots of educational disparity in Brazil today, showing how access to public education was consistently denied even to free Blacks living in Brazil. At the same time, he connects the fact with how late the country implemented affirmative-action policies, only in the early 2000s, and how they are still a reason for division in society today.

Besides Querino, the project introduces the audience to figures such as Maria Felipe de Oliveira, a Black woman who played a decisive role in the battles of the war of independence at Bahia. Also, figures such as Father José Maurício Nunes Garcia, a musician and composer who conducted the mass that celebrated Brazil’s elevation from a colony to United Kingdom of Portugal.

What most surprised Rogero in his research work, however, was the observation that Brazil could have gotten rid of slavery long before 1888. In 1831, under pressure from England, Brazil prohibited the trafficking of enslaved people. The law, considered revolutionary for the time, guaranteed citizenship and freedom to people in slavery conditions brought to Brazil as of that date. But it was never complied with.

“There was a big national agreement to disregard this law until at least 1850, when a new law again prohibits human trafficking. The people who had entered since 1831, some 800,000, were supposed to be freed because their status was illegal. But a new big elite agreement kept them enslaved. When we get to 1888, abolition benefits mostly the descendants of those who arrived after 1831, and who, by law, should have been freed many years earlier,” Rogero said.

Historian Ynaê Lopes dos Santos, from the Fluminense Federal University, acted as a consultant for the Querino Project. She believes the significant audience numbers demonstrate a fundamental need to revisit Brazil’s history critically.

“One of the great accomplishments of Projeto Querino is making this critical perspective very accessible, as well as the stories that have been systematically silenced from the black population, showing that history is a field in dispute,” Lopes dos Santos told LJR. “In this sense, the Querino Project seems to be a fundamental tool for understanding Brazil today. A Brazil that is, without a doubt, a consequence of a set of options and political choices made by the Brazilian elite.”

Multiplatform

Unlike Project 1619, originally conceived for magazine format and later transformed into a podcast, the Querino Project had its genesis as a podcast and only later generated text and image content, with feature stories and photographs published in the magazine Piauí, notable for its in-depth journalism. In the magazine, the choice of the podcast format as a priority was to expand access to the content.

“A podcast is free. Anyone with any cell phone can listen, they can listen to Querino. In addition, spoken media speaks directly to our ancestry and the orality of Afro-descendant people, which is very beautiful,” Rogero said. “When we do the podcast, it can be the hardest journalistic subject possible, but we have to make it like storytelling.”

The Querino Project was funded by the Ibirapitanga Institute, through a grant of R$626,808.51 (equivalent to USD 125,361.70). This amount covered the work of more than two years of a team of 40 people during the research and production of the podcast, and also the dissemination.

Like 1619, the Querino Project will also become a book, and there are conversations with video production companies for an audiovisual format adaptation. Rogero is also working to adapt the content for educational purposes, as he has heard from history teachers who are already using the podcast in their classrooms.

“Querino will continue for the next few years and our big focus is how to get this content into schools, especially public schools. Many teachers are already using the podcast in the classroom, although the language is not ideal. It’s a big concern of mine to make this content reach young people of school age,” Rogero said. “Querino can’t account for everything, but it’s our contribution, so that a more complete and complex version of the story can be known.”