Preface to Black Atlantic Crossings

This is an updated and expanded translation of Travessias no Atlântico Negro: reflexões sobre Booker T. Washington e Manuel R. Querino, released by the Editora da Universidade Federal da Bahia (EDUFBA) in 2020. That year also saw the birth of my grandson John Benjamin, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the beginning of the global Black Lives Matter movement, which transformed what was once considered “niche” research into a highly relevant study. I now see this book as a weapon against historical erasure and a staunch defence of affirmative action and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), which are facing unprecedented assaults in the USA.

According to Florida’s “Stop WOKE Act,” any book (fiction or non-fiction) that makes White people feel uncomfortable about their country’s slaveholding past should be suppressed. Florida’s State Academic Standards—Social Studies (2023) even recommend teaching middle-school students how enslaved people benefited from slavery because, “in some instances,” it enabled them to learn useful skills.[1] Also, as I was translating the original Portuguese edition, the Supreme Court of the United States effectively gutted affirmative action in that country.

On January 21, 2025, President Donald J. Trump issued an executive order dismantling DEI initiatives across federal agencies, urging similar action in the private sector. This resulted in the removal of references to Black, Brown, LGBTQ+ individuals, and women, from government websites. That decree, followed by criticism of the Smithsonian Museum’s efforts to debunk pseudoscientific racism, further amplified this book’s relevance.

In Brazil, former president Jair Messias Bolsonaro attempted to gut higher education—particularly the Humanities—and expressed hostility towards Black civil rights and affirmative action. As a result of his policies, many Black Brazilian students dropped out or simply stopped aspiring to a university degree. Now that Bolsonaro is out of office and may even go to prison for an alleged coup attempt, the Lula administration is undoing some of the damage wrought during Bolsonaro’s time in office. Nevertheless, there is still a long way to go.

The landscape of Brazilian academia and publishing has changed substantially since I defended my PhD in Salvador, Bahia, in 2014. Initially, researching Booker T. Washington in Brazil posed considerable challenges, requiring reliance on international sources and archival research at the US Library of Congress. However, my thesis and the Portuguese edition of this book have helped establish Washington’s presence within Brazilian scholarly discourse, as demonstrated by their increasing citation and use in post-graduate programmes. Graciliano Ramos’s bowdlerised translation of Up from Slavery, Memórias de um negro (retitled Memórias de um negro americano), is back in print for the first time since the 1940s (Washington’s best-known autobiography still awaits a fresh and more objective rendering).

Efforts to reverse the erasure of Black people from history should never abate, and sometimes, they are rewarded. I wish I had made a note of the date, but the moment I felt that Manuel Querino had finally regained his rightful place in Brazilian history was when Lula—then a presidential candidate—mentioned his name along with the usual pantheon of illustrious Black Brazilians, such as Machado de Assis, Teodoro Sampaio, and Luiz Gama.

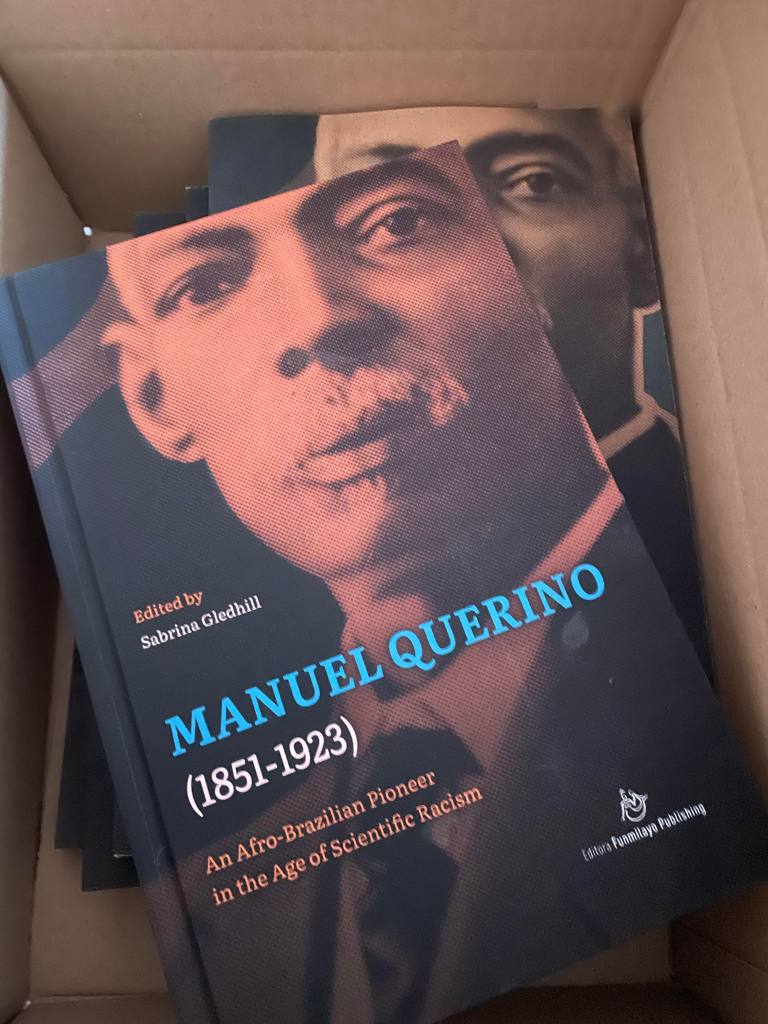

The year 2020 saw two publications on Querino—a book on his studies of Bahian cuisine by Jeferson Bacelar and Carlos Alberto Dória, published in Brazil, and Manuel Querino (1851-1923): An Afro-Brazilian Pioneer in the Age of Scientific Racism, an anthology of essays by several authors which I edited and published in Portuguese and English in Brazil (through the Sagga Editora publishing house) and the UK.

Gláucia Maria Costa Trinchão and Suely dos Santos Souza published the edited volume Os saberes em desenho do professor Manuel Raymundo Querino, on his geometric design textbooks, in 2021. It includes reproductions of those illustrated works—an invaluable contribution, as the original editions are rare.

The Afro-Brazilian polymath’s profile was raised significantly in 2022 by the Projeto Querino podcast. Inspired by The New York Times’s 1619 Project, it follows in Querino’s footsteps by increasing awareness of Black people’s role in Brazilian history—including Querino’s own contributions.[2]

In 2023, the 100th anniversary of his death, Querino received several tributes. The video maker Isis Gledhill produced a documentary on his life, including interviews with leading Querino scholars, and with the organisers and presenters of the Projeto Querino podcast, the journalist Tiago Rogero and the historian Ynaê Lopes dos Santos. The conductor and composer Fred Dantas wrote a piece for brass band called “Dobrado Manuel Querino” that was first performed during the celebrations of the bicentennial of Bahia’s Independence on the 2nd of July, a date that was particularly dear to Querino’s heart.

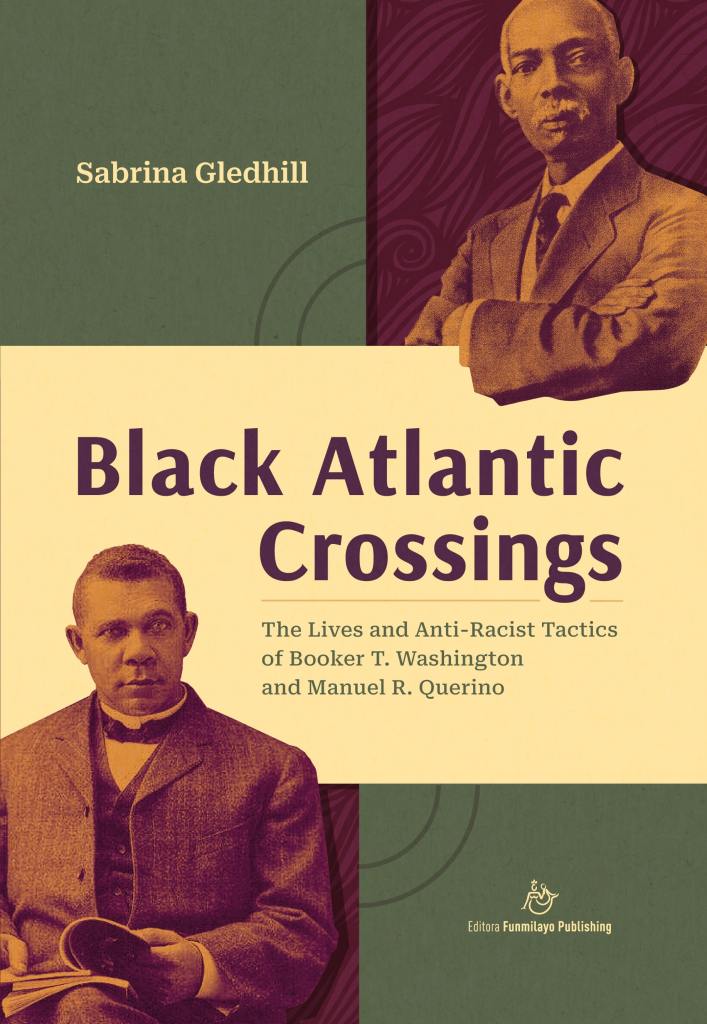

In 2024, I edited and published more two edited volumes inspired by Querino and including translations of his work: The Need for Heroes: Black Intellectuals Dig Up Their Past, and Heroes Sung and Unsung: Black Artists in World History. Along with Manuel Querino (1851-1923) and this monograph, they form part of Funmilayo’s Unsung Heroes in Black History series.

Although I began researching this book in the early 2000s, and some of its contents date back to my MA studies on Brazilian race relations in the 1980s, its message feels more urgent than ever. I hope this comparison of the lives and anti-racist tactics of Booker T. Washington and Manuel R. Querino will point up the fact that reparations are still due to the descendants of enslaved Africans in the United States and Brazil. Affirmative action remains a crucial tool for addressing the enduring legacy of racial injustice.

Sabrina Gledhill

Black Atlantic Crossings will be available as a Kindle e-book on 14 April 2025 and on Amazon and other booksellers as a paperback and hardback on 1 May 2025.

[1] Florida’s State Academic Standards—Social Studies, 2023. SS.68.AA.2.3 “Examine the various duties and trades performed by slaves (e.g., agricultural work, painting, carpentry, tailoring, domestic service, blacksmithing, transportation). Benchmark Clarifications: Clarification 1: Instruction includes how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.” https://www.fldoe.org/core/fileparse.php/20653/urlt/6-4.pdf

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/oct/06/brazil-history-african-brazilians-tiago-rogero-querino-project. The podcast is available (in Portuguese) at https://projetoquerino.com.br/podcast/