Uncategorized

The Legacy of Manuel Querino: Challenging Historical Narratives

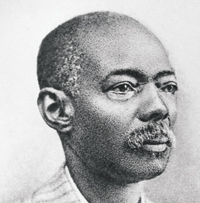

The only book I had in mind back in 2020 was an anthology on Manuel Querino, the Afro-Brazilian scholar I have been studying and writing about since the 1980s. I had just published a book in Portuguese based on my PhD thesis comparing Querino to Booker T. Washington, and I was being urged to publish something about Querino in English. I had also written several essays that had appeared in Brazilian peer-reviewed journals and books over the years and would make a small volume. Then, it occurred to me that Querino’s activities were so varied, covering a gamut of specialisms, that it is impossible for one person to write authoritatively about them all.

Fortunately, I had access to writings by E. Bradford Burns (the first bibliographic essay on Querino published in English), Jeferson Bacelar and Carlos Doria (on his pioneering study of Bahian cuisine), Eliane Nunes (on his contributions to art history), Jorge Calmon (on his involvement in labour mobilisation and politics), and Christianne Vasconcellos (on his use of photographs in anthropology) to add to my own writings . The result was Manuel Querino (1851-1923): An Afro-Brazilian Pioneer in the Age of Scientific Racism, a compendium that has also been published in Portuguese (without Burns’s essay, due to translation rights), and has been very well received.

That book was published in 2021, during the Covid pandemic. Lockdown was a wonderful opportunity to focus on organising and translating the anthology. In the years since, I have worked on translating and updating a monograph based on my PhD thesis, which has been in peer review with another publisher for several months. The Unsung Heroes series began with the second volume, which I first approached as “something to do” while awaiting the verdict on my own book. It all started with Querino, naturally. I had originally intended to publish my translation of one of his most significant works (for me), O colono preto como fator da civilização brasileira, translated as The African Contribution to Brazilian Civilisation.

First, I was intrigued by parallels between Querino’s story and that of Arthur (born Arturo) Schomburg. Then, I started wondering which works by W. E. B. Du Bois, Carter G. Woodson, Booker T. Washington, and other Black thinkers were comparable to Querino’s essay, which demands recognition for the achievements of Africans and their descendants. Instead of being seen as passive sources of manual labour, Querino asserted that they contributed knowledge they brought from their homelands, such as mining and metalworking, as well as helping maintain Brazil’s territorial integrity as soldiers. He also emphasised their ingenuity and courage in breaking free from the bonds of slavery to form their own communities, known as quilombos in Brazil.

That initial curiosity led to a gold mine of works on Black soldiers and maroons, which I added to Querino’s essay to produce The Need for Heroes: Black Intellectuals Dig Up their Past, published in June 2024. I realised that the concept of Unsung Heroes, inspired by the title of Elizabeth Ross Haynes’s book of children’s stories, extended to the anthology on Querino. He was well known in life, having achieved such renown in Brazil that several newspapers published his obituary in his home state (Bahia), Rio de Janeiro, and other parts of the country. Representatives of trade unions and academia attended his funeral, which was also covered by the press. But since the 1930s, he had been gradually forgotten, and if remembered at all, thought of as a lightweight scholar, the minor author of a few pamphlets, and even illiterate. There seemed to have been a deliberate effort on the part of the “hegemonic narrative” to rewrite his story as that of a poor, ill-educated Black man who made a stab at anthropology but didn’t quite succeed. This disinformation was convenient because he already contradicted the commonly held notion that all Blacks in Brazil were enslaved until Abolition in 1888, and since then had been nothing but vagrants, thieves, and scoundrels – an image still maintained in the media.

While the eminent Brazilian historian Flavio Gomes was writing the afterword for The Need for Heroes (it was worth the wait), I started putting together works that hadn’t quite fit in that collection and adding many more. Once again, I started with Querino, who is considered the Brazilian Vasari because his pioneering works on the history of art in Bahia were based on biographies of artists. The result was Heroes Sung and Unsung: Black Artists in World History, a compendium of works by Querino, as well as Arthur Schomburg, W. E. B. Du Bois, Booker T. Washington, Benjamin Brawley, James M. Trotter, Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, and others, with a foreword and afterword by brilliant contemporary artists and writers: Mark Steven Greenfield, from the USA, and Ayrson Heráclito and Beto Heráclito, from Brazil. It joins the first two titles, Manuel Querino (1851-1923): An Afro-Brazilian Pioneer in the Age of Scientific Racism and The Need for Heroes: Black Intellectuals Dig Up their Past, which are also available in paperback, hardcover, and Kindle e-book editions.

When I’m asked what’s next, the answer seems obvious—an anthology about Black women heroes, “sung and unsung.” I might even reclaim the word “heroine.” I haven’t come up with a title yet, and I may have to write most of the bios myself, but it is something to look forward to. Watch this space.

This post is an adaptation of an essay published in Heroes Sung and Unsung

The Role of Black Heroes in America’s Freedom Journey

A moving response to The Need for Heroes: Black Intellectuals Dig up their Past

The book is extremely timely, given the state/conditions of the politics of the US currently.

It is good having all this detailed background information in one place. It provides historical background/examples of how and why the current politic and society have reached this point.

The essays of the authors and stories of various heroes humanize them: enslaved Harriet Tubman doing housework to the displeasure of her mistress, Booker T. Washington’s friendship with Charles Banks of Mount Bayou, Mississippi and with Bishop George W. Clinton of Lancaster, South Carolina, the town where my ancestors lived.

Learning about individuals of the years immediately after slavery making their way in the post-slavery era in US is extremely important, not to mention those who struggled for Freedom before the Civil War. Learning about Blacks who were not enslaved, like Crispus Attucks, but struggled for the freedom during American Revolutionary War was eye opening, as well as details of abuses/discrimination against Blacks after the 1812 war.

For myself, I can say “Heroes” makes me want to know and read more about Black people/heroes, past and present, who have contributed to the march forward to Freedom. A copy of The Need for Heroes should be in the home of all “Black Folk” and other Americans!

Barry Stinson

Latest News

Thanks to Google Scholar, I’ve just discovered that academic journals have published reviews of two Funmilayo titles: Travessias no Atlântico Negro: Reflexões sobre Booker T. Washington e Manuel R. Querino (also published by Edufba in Brazil) and Manuel Querino (1851-1923): An Afro-Brazilian Pioneer in the Age of Scientific Racism, the anthology also published in Brazil by Sagga Editora.

Travessias was reviewed in the Bulletin of Latin American Research (BLAR) last October, and the review of the anthology just came out this month (August 2024) in the Hispanic American Historical Review (HAHR) in Portuguese.

Querino is finally reaching academic outlets outside Brazil. The first time, that I know of, was when E. Bradford Burns’s bibliographical essay about the Afro-Brazilian polymath came out in The Journal of Negro History in the 1970s (that essay is also included in the Manuel Querino anthology).

Meanwhile

We’re putting the finishing touches on the latest addition to the Unsung Heroes in Black History series – Heroes Sung and Unsung: Black Artists in World History is in press and scheduled for publication in September. The illustrations include a self-portrait of the photographer Addison Scurlock (above). Here is another illustration, included in the afterword by Ayrson Heráclito and Beto Heráclito:

Xango Eyes, by Bauer Sá (reproduced with permission from the photographer)

From Brazil to The Bookery

Many had a productive ‘lockdown,’ but how many Kirtonians can say that they published three books in two languages and started a publishing house in their home office? “Well, technically, it’s two books,” the author and publisher observes, because she produced two editions of a similar collection of essays. Only one of those is in English, and it is now for sale at The Bookery in Crediton’s High Street.

It was in February 2020 that, while awaiting the birth of her second grandson, local resident Dr Sabrina Gledhill signed a contract in Brazil to publish a book in Portuguese based on her PhD thesis. That work, which Dr Gledhill is now translating and adapting for English-speaking readers, focusses on two Black leaders, Booker T. Washington in the US, and Manuel R. Querino in Brazil. The founder of what is now Tuskegee University, Washington is well known around the world, but he had been largely forgotten in Brazil. Querino, on the other hand, was famous in Brazil during his lifetime, but has only recently been re-evaluated and restored to his rightful place in the ranks of pioneering Brazilian anthropologists and art historians.

The book was launched in Salvador, Bahia, in September 2020. Despite travel restrictions and thanks to the wonders of the Internet, Dr Gledhill was able to promote the book from her library near Crediton, from where she took part in round-table discussions and gave interviews to Brazilian TV and radio hosts.

Asked when she would start publishing in English, which is, after all, her native tongue, Dr Gledhill then edited a collection of essays on Manuel Querino by E. Bradford Burns and Jeferson Bacelar (respectively her MA and PhD supervisors) and other authors, including her own work, which had been published in Brazilian peer-reviewed journals. The reasoning was that Querino’s activities were so varied that it takes a number of specialists to do them justice. Dr Gledhill translated most of the essays from Portuguese into English, but since she already had the originals in Portuguese ready for publication, she thought, why not publish a Brazilian edition as well?

The result was that, by the end of 2021, when travel restrictions eased and she was finally able to visit her Brazilian family again, two more books were released in Brazil and the UK. The publisher of the English edition is Editora Funmilayo Publications, based in Crediton. Manuel Querino (1851-1923): An Afro-Brazilian Pioneer in the Age of Scientific Racism is available as an e-book, and in paperback and hardback editions on Amazon, Alibris and, of course, at The Bookery.

Published in the Crediton Courier on 25 August 2022

O resgate de Manuel Querino

Intelectual afrodescendente lutou contra os estereótipos de sua época e valorizou a contribuição do negro na formação do Brasil

Suzel Tunes, da Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

Na introdução de seu livro Artistas baianos, publicado em 1911, Manuel Raymundo Querino escreveu: “A Bahia possui muita preciosidade na poeira do esquecimento”. Durante muito tempo, a memória do artista, historiador, etnólogo, escritor e político negro, nascido livre em 1851 – antes, portanto, da abolição da escravatura –, também ficou imersa nessa poeira.

Querino desfrutou de surpreendente prestígio na sociedade onde imperavam ideologias racistas: sua morte, em 1923, foi registrada por vários jornais, e a seu enterro compareceram políticos e representantes do Instituto Geográfico e Histórico da Bahia e da Escola de Belas Artes. Mas com o passar dos anos sua imagem foi sendo desvalorizada, até o esquecimento. Pioneiro em diversas áreas do saber, começou a ser rotulado como autodidata. “Na época, seria o mesmo que dizer que ele era iletrado. Seus livros começaram a ser chamados de opúsculos”, relata a historiadora inglesa Sabrina Gledhill, ainda indignada com a indiferença, mais de 40 anos depois de ter começado a estudar essa figura histórica.

Hoje, a academia reconhece Querino como o primeiro historiador da arte na Bahia e um dos pioneiros no estudo de história da arte no Brasil. Autor de um dos primeiros livros sobre culinária baiana, participou da criação, como aluno fundador, do Liceu de Artes e Ofícios da Bahia e da Escola de Belas Artes e criou dois jornais (A Província, em 1887, e O Trabalho, em 1892). Foi um dos fundadores da Liga Operária Baiana (1876) e do Partido Operário (1890) e conselheiro municipal de Salvador.

Sua contribuição mais marcante, como os pesquisadores são unânimes em identificar, está nos textos em que destaca o protagonismo dos africanos e de seus descendentes na formação da sociedade brasileira. “Ele desmentiu a ideia de que o escravizado havia sido uma mão de obra passiva, detalhando os conhecimentos trazidos da África, inclusive sobre mineração. Nenhum afrobrasileiro, até então, havia expressado sua perspectiva da história do Brasil”, afirma Gledhill.

Antes de Querino, apenas dois intelectuais de ascendência europeia – o advogado fluminense Alberto Torres (1865-1917) e o médico sergipano Manoel Bonfim (1868-1932) – haviam contestado teorias como o “racismo científico” e o “darwinismo social”. Essas pseudociências postulavam a superioridade europeia numa escala evolutiva e condenavam a miscigenação, afirmando que a mistura de raças provocava a degeneração física e intelectual do povo.

Foi nesse contexto que Manuel Querino publicou o livro O colono preto como fator da civilização brasileira, em 1918, no qual afirmava: “o Brasil possui duas grandezas reais: a uberdade do solo e o talento do mestiço”. Foi graças a essa frase que Gledhill descobriu Querino, nos anos 1980. Ela buscava um tema para seu mestrado em estudos latino-americanos pela Universidade da Califórnia em Los Angeles (Ucla), nos Estados Unidos. “Eu estava lendo Tenda dos milagres, de Jorge Amado [1912-2001], ainda em inglês, e encontrei essa citação de Querino como epígrafe do livro. Quis saber quem era ele e fui perguntar ao meu orientador [o historiador norte-americano Edward Bradford Burns].” Burns (1933-1995) conhecia bem o personagem; fora o primeiro pesquisador estrangeiro a estudar a vida e a obra de Manuel Querino, ainda na década de 1970. Estava escolhido o objeto de pesquisa de Gledhill.

Chegando ao Brasil, já em busca de um tema para o doutorado, Gledhill conheceu pessoalmente Jorge Amado: “Ele me confirmou que Querino foi uma das inspirações para a criação do personagem Pedro Archanjo, de Tenda dos milagres”. No livro, lançado em 1969, Archanjo é um pesquisador mestiço que tem, como seu principal opositor, o catedrático Nilo Argolo, arauto da superioridade da raça branca – inspirado no antropólogo e médico Raimundo Nina Rodrigues (1862-1906), um dos primeiros a abordar a influência africana na cultura brasileira e expoente brasileiro do movimento eugenista, que pregava contra a miscigenação.

“Jorge Amado retrata Pedro Archanjo como uma pessoa múltipla e assim era Manuel Querino. Ele não foi um só, foi vários”, diz a historiadora Maria das Graças de Andrade Leal, da Universidade do Estado da Bahia (Uneb) e autora de um amplo estudo biográfico sobre o baiano que transitava em diversos espaços sociais, como operário e intelectual adepto do candomblé e defensor da capoeira. “Por meio de sua vida, a vida de muitos outros afrodescendentes pôde ser trazida à luz, possibilitando uma versão da história pela ótica do oprimido.”

Nascido em Santo Amaro da Purificação, em 28 de julho de 1851, aos 4 anos Querino ficou órfão de mãe e pai, vítimas de uma epidemia de cólera. De acordo com as pesquisas de Leal, uma vizinha o teria acolhido, mas, sem condições de mantê-lo, solicitou ajuda ao Juiz de Órfãos, prática comum à época. O juiz encaminhou a criança ao professor, jornalista e político Manoel Correia Garcia (1815-1890), nomeando-o seu tutor. “Na epidemia de cólera, houve o movimento de uma determinada elite baiana para tutelar crianças órfãs, que foram muitas”, diz ela. O menino não morou com o tutor, mas ele custeou seus estudos – o que, certamente, definiu os rumos de sua história.

“O estudo salvou a vida dele”, afirma Gledhill. Aos 17 anos, Querino foi recrutado para a Guerra do Paraguai (1864-1870). Ele estava, então, no Piauí – ao que tudo indica, fugindo do recrutamento forçado a que eram sujeitos os homens livres pobres. Conseguiu não ir para o front, provavelmente por ser um dos poucos soldados que sabia ler e escrever. Serviu como escrevente no Rio de Janeiro e, ao final da guerra, voltou a Salvador.

Querino trabalhava durante o dia como pintor-decorador e estudava à noite. Cursou humanidades no Liceu de Artes e Ofícios da Bahia e desenho na Academia de Belas Artes. Na Academia, que passaria a se chamar Escola de Belas Artes no período republicano, recebeu o diploma de desenhista em 1882. Prosseguiu para o curso de arquitetura, mas não pôde concluí-lo pela ausência de professores que lecionassem as duas últimas disciplinas que faltavam para sua formação. Ainda assim, seu primeiro trabalho acadêmico foi divulgado pela imprensa local: o projeto “Modelos de casas escolares adaptadas ao clima do Brasil”, elaborado em 1883 para o Congresso Pedagógico do Rio de Janeiro.

Querino começou sua atuação política a partir do movimento operário. Segundo o museólogo e historiador de arte Luiz Alberto Ribeiro Freire, da Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA), o convívio com o meio intelectual não o fez rechaçar suas origens e expressões da cultura popular. Práticas populares como o samba, o candomblé e a capoeira, reprimidas pelo governo no afã de branquear e civilizar a sociedade, foram valorizadas em seus escritos. “Em geral havia uma espécie de aculturação quando pessoas das camadas populares chegavam às instituições da elite; elas adquiriam a ideologia hegemônica. Mas Querino nunca deixou de se posicionar na classe social como artista operário”, diz Freire. Em 1874, com apenas 23 anos, seria um dos fundadores da Liga Operária Baiana.

Após se formar, ele foi professor de desenho industrial no Liceu de Artes e Ofícios, além de pintor-decorador. Segundo ele mesmo descreve no livro Artistas baianos – Indicações biográficas, seus trabalhos incluíam a pintura de casas públicas e particulares, bondes e do hospital da Santa Casa de Misericórdia. Ele foi auxiliar do pintor espanhol Miguel Navarro y Cañizares (1834-1913), responsável pelas imagens do pano de boca do Teatro São João. Freire explica que o pintor-decorador pintava murais artísticos em paredes, e não se preservou nenhum registro desses trabalhos. Já o pano de boca (pintura feita em tecido para cobrir o palco do teatro antes da apresentação) queimou-se em um incêndio que destruiu o Teatro São João, em 1923.

O maior legado do intelectual baiano está, portanto, em seus estudos sobre história, cultura e folclore da Bahia e do povo africano. “Nina Rodrigues e Manuel Querino foram considerados as maiores autoridades sobre a cultura afrobaiana por seus contemporâneos”, afirma Gledhill. Enquanto Rodrigues continuou lembrado e reverenciado, Querino começou a ser menosprezado pela academia ou tratado com paternalismo. O médico e etnólogo Artur Ramos (1903-1949) o classificou como um “pesquisador honesto, um trabalhador incansável”, mas “sem o rigor metodológico e a erudição científica de Nina Rodrigues”. Para a pesquisadora, racismo e preconceito de classe explicam a atitude.

Freire avalia que a maior facilidade de acesso de afrodescendentes à universidade, sobretudo a partir dos anos 2000, possibilitou o resgate. Desde 2014 ele coordena um projeto que vem dando continuidade ao trabalho do primeiro historiador da arte baiana: o Dicionário Manuel Querino de arte na Bahia. O dicionário eletrônico foi criado por um grupo de pesquisadores da UFBA e da Universidade Federal do Recôncavo da Bahia (UFRB), com apoio da Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado da Bahia (Fapesb). Conta com 362 verbetes sobre artistas que nasceram ou trabalharam no estado, além de movimentos e patrimônios artísticos do estado. “A maior conquista do dicionário foi honrar a memória de Manuel Querino, levando o seu trabalho adiante”, diz Freire, que já tem um novo projeto em mente, só esperando pela aposentadoria do magistério, daqui a dois anos. “Minha ideia é publicar uma Caixa Querino, reunindo todos os seus livros e os que falam sobre ele.”

No campo do audiovisual, Querino também tem herdeiros. Em 2023, no centenário de sua morte, foi lançado o documentário Querino – 100 anos, no YouTube. O filme é uma produção independente, com recursos captados por meio do site de financiamento coletivo Catarse, com direção de Isis Gledhill, que herdou da mãe, Sabrina, a paixão pela história de seu conterrâneo. Isis nasceu e cresceu em Salvador, cidade que, além de palco de pesquisa, se tornou um lar para Sabrina ao longo de 28 anos.

Com o mesmo propósito de incluir o negro na história como protagonista, em agosto de 2022 foi lançado o Projeto Querino, uma série de podcasts criada pelo jornalista Tiago Rogero e desenvolvida por uma equipe de 40 pessoas. Com produção da Rádio Novelo, o projeto com oito episódios ganhou versão escrita pela revista Piauí e foi um dos vencedores do Prêmio Jornalístico Vladimir Herzog de 2023, na categoria Produção Jornalística em Áudio.

A iniciativa é inspirada no “1619 Project”, da jornalista norte-americana Nikole Hannah-Jones, que reformula a história dos Estados Unidos a partir das consequências da escravidão: 1619 é o ano em que os primeiros escravizados chegaram ao país. Quando Rogero e equipe conheceram a história de Querino – retratada no episódio 4, em que se discute o direito à educação –, encontraram o nome ideal para o projeto brasileiro. “Ele simboliza muito o que a gente tentou fazer em vários aspectos, contando a história do Brasil sob um olhar afro-centrado, algo que já fazia no final do século XIX e começo do século XX”, comenta o jornalista.

E novos projetos influenciados pelo intelectual multifacetado estão a caminho. Com a parceria da Fundação Itaú Social e do Centro de Estudos das Relações de Trabalho e Desigualdades (Ceert), o conteúdo do podcast jornalístico está sendo adaptado para uso em sala de aula, com sugestão de atividades e leituras complementares. Rogero também escreveu um livro aprofundando o conteúdo do podcast (que deverá ser lançado em setembro, pela Editora Fósforo) e já fechou outro contrato para a publicação de uma graphic novel de ficção. “Ela será ambientada no ‘universo’ do Projeto Querino, parte de um esforço para alcançar também públicos mais jovens”, revela o autor.

Artigo científicos GLEDHILL, Sabrina. Representações e respostas: Táticas no combate ao imaginário racialista no Brasil e nos Estados Unidos na virada do século XIX. Sankofa ‒ Revista de História da África e de Estudos da Diáspora Africana. São Paulo, Brasil, v. 4, n. 7, p. 45–72, 2011.

Livros GLEDHILL, Sabrina (org.). (Re)apresentando Manuel Querino 1851-1923: Um pioneiro afrobrasileiro nos tempos do racismo científico. Editora Funmilayo, 2021. GLEDHILL, Sabrina. Travessias no Atlântico negro: Reflexões sobre Booker T. Washington e Manuel R. Querino. Salvador: EDUFBA, 2020. LEAL, M. G. A. “Manuel Querino: Entre letras e lutas Bahia 1851-1923.” Tese apresentada ao Programa de Estudos Pós-graduados em história da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC-SP) para obtenção do título de doutor em história social, 2004. Editado em 2009 pela editora Annablume (esgotado). QUERINO, Manuel. A arte culinária na Bahia. Salvador: Progresso Editora, 1957. QUERINO, Manuel. O colono preto como fator da civilização brasileira. São Paulo: Cadernos do Mundo Inteiro. 2 ed. 2018. QUERINO, Manuel. Artistas bahianos. Indicações biographicas. Bahia: Officinas de Empreza. 2 ed. 1911. QUERINO, Manuel. A raça africana e os seus costumes. Salvador: Livraria Progresso Editora. Coleção de Estudos Brasileiros, 1955.

Este texto foi originalmente publicado por Pesquisa FAPESP de acordo com a licença Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND. Leia o original aqui.

September is nearly here

Some AI art while we’re waiting for the proofs to arrive…

Unsung Heroes: The Legacy of Manuel Querino and Beyond

I launched the Unsung Heroes in Black History series without realising it was a series at all. It started with an anthology on Manuel Querino, the Afro-Brazilian scholar I have been studying and writing about since the 1980s. I realised that Querino’s activities were so varied, covering a gamut of specialisms, that it is impossible for one person to write authoritatively about them all. Fortunately, I had access to writings by E. Bradford Burns (the first bibliographic essay on Querino published in English), Jeferson Bacelar and Carlos Doria (on his pioneering study of Bahian cuisine), Eliane Nunes (on his contributions to art history), Jorge Calmon (on his involvement in labour mobilisation and politics), and Christianne Vasconcellos (on his use of photographs in anthropology) to add to essays of my own that had appeared in Brazilian peer-reviewed journals and books over the years. The result was a compendium that has been published in Portuguese (without Burns’s essay, due to translation right issues) and English, and has been very well received.

That book was published in 2021, during the Covid pandemic. Lockdown was a wonderful opportunity to focus on organising and translating the anthology. In the years since, I have worked on translating and updating a monograph based on my PhD thesis, which has been in peer review since September of last year. The Unsung Heroes series began with the second volume, which I first approached as “something to do” while awaiting the verdict on my own book. It all started with Querino, naturally. I had originally intended to publish my translation of one of his most significant works (for me), O colono preto como fator da civilização brasileira, translated as The African Contribution to Brazilian Civilisation.

First, I was intrigued by parallels between Querino’s story and that of Arthur (born Arturo) Schomburg. Then, I started wondering which works by W. E. B. Du Bois, Carter G. Woodson, Booker T. Washington, and other Black thinkers were comparable to Querino’s essay, which demands recognition for the achievements of Africans and their descendants. Instead of being seen as passive sources of manual labour, Querino asserted that they contributed knowledge they brought from their homelands, like mining and metalworking, as well as helping protect Brazil’s territorial integrity as soldiers. He also emphasised their ingenuity and courage in breaking free from the bonds of slavery to form their own communities, known as quilombos in Brazil.

That initial curiosity led to a gold mine of works on Black soldiers and maroons, which I added to Querino’s essay to produce The Need for Heroes: Black Intellectuals Dig Up their Past, published in June 2024. I realised that the concept of Unsung Heroes, inspired by the title of Elizabeth Ross Haynes’s book of children’s stories, extended to the anthology on Querino. He was well known in life, having achieved such renown in Brazil that several newspapers published his obituary in his home state (Bahia), Rio de Janeiro, and other parts of the country. Representatives of trade unions and academia attended his funeral, which was also covered by the press. But since the 1930s, he had been gradually forgotten, and if remembered at all, thought of as a lightweight scholar, the minor author of a few pamphlets, and even illiterate. There seemed to have been a deliberate effort on the part of the “hegemonic narrative” to rewrite his story as that of a poor, ill-educated Black man who made a stab at anthropology but didn’t quite succeed. This disinformation was convenient because he already contradicted the commonly held notion that all Blacks in Brazil were enslaved until Abolition in 1888, and since then had been nothing but vagrants, thieves, and scoundrels – an image still maintained in the media.

While the eminent Brazilian historian Flavio Gomes was writing the afterword for The Need for Heroes (it was worth the wait), I started putting together works that hadn’t quite fit in that collection and adding many more. Once again, I started with Querino, who is considered the Brazilian Vasari because his pioneering works on the history of art in Bahia were based on biographies of artists. The result was Heroes Sung and Unsung: Black Artists in World History, a compendium of works by Arthur Schomburg, W. E. B. Du Bois, Booker T. Washington, Benjamin Brawley, James M. Trotter, and others, with a foreword and afterword by two brilliant contemporary artists, respectively Mark Steven Greenfield and Ayrson Heraclito. It is due for publication in September 2024. In the meantime, Manuel Querino (1851-1923): An Afro-Brazilian Pioneer in the Age of Scientific Racism and The Need for Heroes are available in paperback, hardcover, and Kindle e-book editions through Amazon and other online booksellers.

Sabrina Gledhill