Marcos Rodrigues

MA in Ethnic and African Studies, UFBA

ORCID: 0000 0002-6662-2350

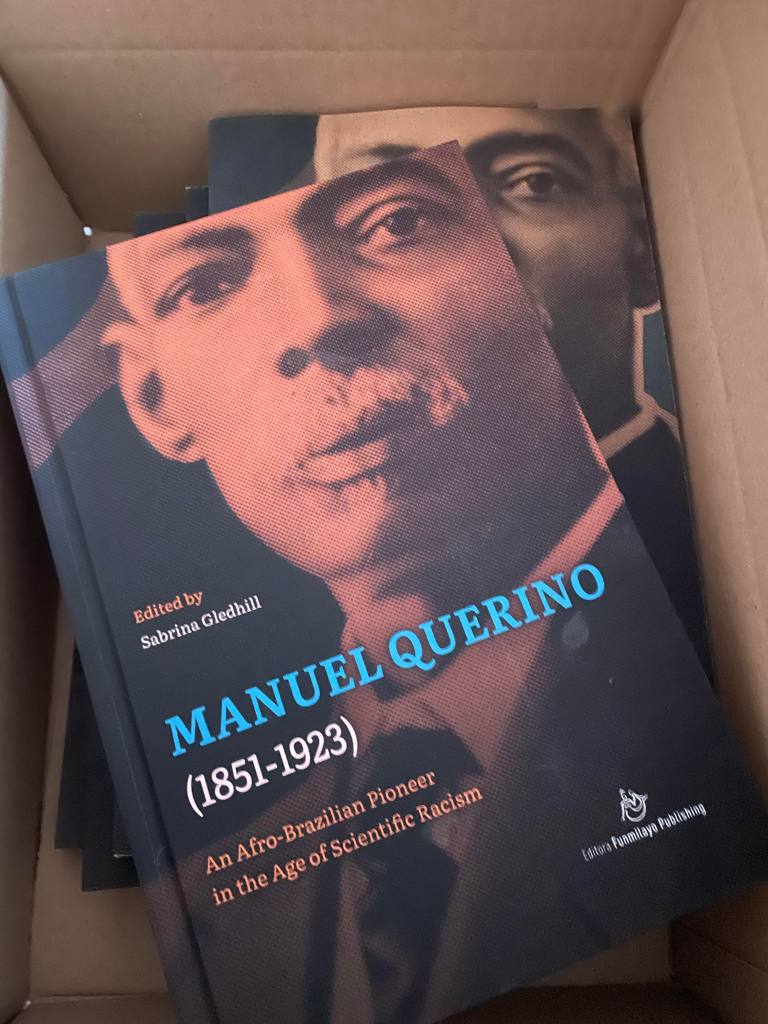

Review of GLEDHILL, Sabrina (ed.). Manuel Querino (1851-1923): An Afro-Brazilian Pioneer in the Age of Scientific Racism. Crediton: Funmilayo, 2021.[1]

Edited by the independent scholar Sabrina Gledhill, this book introduces—or reintroduces—the life and work of the Brazilian intellectual and activist Manuel Querino (1851-1923), a pioneer in the construction of the civilizing Afro-Brazilian discourse in the age of scientific racism. Born in Santo Amaro, Bahia, in colonial times, Querino can certainly be considered the forefather of the struggle for affirmative action for the Black population, based on the spaces he occupied as an educator, labour leader, politician, ethnologist, and writer.

It was a time when evolutionist theories affirmed the classification of inferiority and the prospect of extinction for the Black population, favouring European immigration and the culture of “whitening.” Manuel Querino emerged as a pioneer in several advanced lines of thought, such as ethnology, food anthropology, art history, and the struggle for affirmative action. These qualities marked his trajectory in this book, which also includes essays by E. Bradford Burns, Jorge Calmon, Eliane Nunes, Cristianne Vasconcellos, Jeferson Bacelar, and Carlos Dória.

With the aim of presenting a many-sided biographical analysis against a framework of concepts and definitions of blackness from an evolutionary standpoint, this book was organised from the perspective of scholars from the fields of politics, history, anthropology and social science who focussed on shedding light on Manuel Querino’s legacy. This anthology is also the result of the interconnected movement of humanists from different generations, which certainly contributes in grand style to the reintroduction of its protagonist and his multifaceted trajectory.

Constructing a discourse involves transgressing, deconstructing, and selecting the paradigm or category of thought to be followed. This foray by Sabrina Gledhill dates back to her previous book, Travessias no Atlântico Negro: Reflexões sobre Booker T. Washington e Manuel Querino (Black Atlantic Crossings: Reflections on Booker T. Washington and Manuel R. Querino; Edufba, 2020), and her participation in other edited volumes, with the aim of spotlighting activist intellectuals from the world of the African diaspora. Now, very opportunely, she has written essays and linked them to narratives by other authors to help establish Manuel Querino’s rightful place as a political subject of his time, whose leading role must be explored.

But what is the place which Manuel Querino occupies in the history of the Brazilian arts and culture, specifically in the state of Bahia? Certainly, in this book, there are several clues to follow to obtain an answer from each author’s perspective. In every field of activity, Querino produced a work that has left its mark on our time. Although he was never enslaved, he seems to have constructed a public discourse based on the perspective of Black people in a society that was being transformed after losing its economic foundations, the culture of bondage.

In her introduction, Sabrina Gledhill, a British Brazilianist and award-winning translator educated in the UK, the US, and Brazil, reveals that her interest in Querino began in the early 1980s, when she was looking for a subject for her MA research at UCLA. Putting Manuel Querino’s life and work in context, she keeps a close eye on the path followed by a controversial man who experienced the final phase of the colonial era and the consequences of slavery in the early twentieth century. The author and editor describes Querino as a lone voice, a Black man who won a place among the White elite and tried to use his position to spread a message that few people of his colour could or were willing to deliver.

Few Brazilians followed such an enlightened path as Manuel Querino, now reintroduced to all those who work in the field of social science and are still surprised when he is mentioned. The importance of revitalising this memory comes from his being a pioneer in the fight against scientific racism as dictated by forensic medicine, from underscoring the African influence in Brazilian history, from introducing the field of art history in Bahia, as well as research on the anthropology of food.

Of the nine chapters that make up this book, two, in particular, stand out. Chapter 6, which focuses on the use of photographs in ethnographic studies, is a direct reflection on a debate that is now actively ongoing in anthropology. The author, Christianne Vasconcellos, sheds light on Manuel Querino’s anthropology in his ethnographic studies of Africans in Bahia with an essay that induces the reader to return to the path of recognising and knowing him as a way of understanding our historic process.

Chapter 8 is the key to understanding the origins of what is now known as Bahian cuisine. The scholars and guest authors Jeferson Bacelar and Carlos Dória reveal that Manuel Querino was the first to study Bahian cuisine, giving rise to a segment of food anthropology. Thus, it should be recalled that the tourist attraction now promoted on a grand scale came from the research done by Querino in difficult times marked by a strictly Eurocentric culture in a colonising intellectual market.

Reading that essay easily leads us to reflect on how the African diaspora in the Americas and Caribbean contains thousands of hidden human values that struggled and played a leading role in overcoming adversity, and the effectiveness of post-slavery affirmative action. The civilising discourse that shaped our thinking, always on the basis of European colonisers as a tentacular reinforcement for scientific racism, was already showing its contradictions. Hence, the merit of the narratives gathered here in delving against the grain of invisibility and bringing to light the life and works of Manuel Querino.

This anthology seems to achieve an important objective. It leaves the reader with the desire to find or re-examine Manuel Querino’s work and include him among the main sources in discussions or research that will be forthcoming when the subject is Bahian culture. The objectivity of the essays leads to a sphere of knowledge hitherto neglected by the canonical thought of the intellectual “classics” of the past. Therefore, recent generations are grateful for this act of reparation on behalf of a vibrant historical and cultural legacy that is clearly overlooked.

Certainly, digging into Querino’s life is no easy task for scientific research. The sources consulted and the authors invited to take part in this publication indicate the extent of the activity surrounding a personage who paved the way for ethnological, historical, and artistic studies focused on Africanity and its offshoots in the diaspora. Therefore, this book is also an example of intellectual responsibility.

[1] Adapted from a review of the Brazilian edition.

As I wrote in

As I wrote in