I like to think that I freed a slave – a young girl who was being forced to work as a maid for no pay in Brazil – but looking back, I realised that she was, in her own way, a free agent…

I like to think that I freed a slave – a young girl who was being forced to work as a maid for no pay in Brazil – but looking back, I realised that she was, in her own way, a free agent…

The regulations governing domestic service in Brazil have changed dramatically in recent years, giving maids and nannies nearly all the rights provided to officially employed workers under the country’s draconian labour laws. Their most recent achievement is the right to the Length-of-Service Guarantee Fund (FGTS). Unfortunately, as householders find themselves having to pay their servants the minimum salary plus benefits, and the tax burden rises, many are no longer able to afford full-time, live-in help and are adopting a system more common in the ‘First World’ – having cleaners come by twice a week at most, to avoid the risk of being sued for failing to sign their work papers.

One way of getting around this is bringing in a young girl from the countryside to work as a maid in exchange for an education. Sometimes the bargain is honoured. In many cases, she becomes a modern-day slave.

My elder daughter befriended one such domestic worker, a fourteen-year-old girl I’ll call Bela. She worked for a couple that lived in the flat above ours. Through my daughter, I would hear that, although Bela was allowed to study, her activities were being increasingly curtailed. After a while, she was only allowed to leave the flat to go to the bakery, and made to work every day of the week, including Sunday, when she did the ironing.

Another sad fact about Brazilian maids is that they are often subjected to sexual harassment. I gathered from the news that filtered through my daughter that this underage girl was being sexually stalked by the man of the house. His jealousy might be the reason for her virtual house arrest, as she was even accused of flirting with the baker!

Even worse – again, according to Bela – she did not receive any money directly. The couple claimed to be depositing her wages in a savings account in Bela’s home town, but there was no proof that this was actually the case.

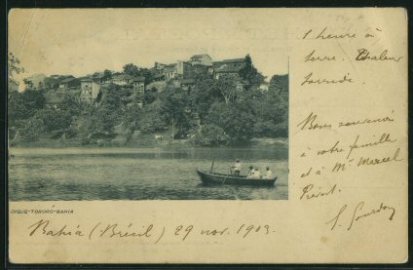

One weekend, I was taking my family with me on a scouting mission to organise a tour of the region for architects who would be planning a resort on the North Coast of Bahia, and invited Bela to go along. My daughter wanted her to go with us to keep her company, and I felt sorry for her, as she was rarely allowed to cross the street, let alone go on a day trip into the countryside. Bela agreed with alacrity, and we all had a good time visiting the colonial landmarks and resorts I selected for the architects’ itinerary.

When we got back, I was startled to hear Bela say that she could not return to her home/workplace because she had left without permission. She seemed fearful of the consequences. I immediately offered to let her stay with us, and she accepted. My daughter was pleased and I thought I had done a good deed. Then things got complicated…